01 なぜ『健康空間』か?-Why Healthy Building?

序

朝7時に起床して朝食を済ませると、約1時間の通勤時間にニュースをチェックしていた。出社後、午前中の業務を済ませると、職場から歩いて約10分のお店でランチを済ませた。午後の業務は片道20分かけての客先での打合せであった。結局、定時内では終わらず、1時間の残業となった。帰宅時間の1時間は疲れるが、少しの満足感に似た感情を伴っていた。夜8時に帰宅してからは家族と過ごすかけがえのない時間である。

本編

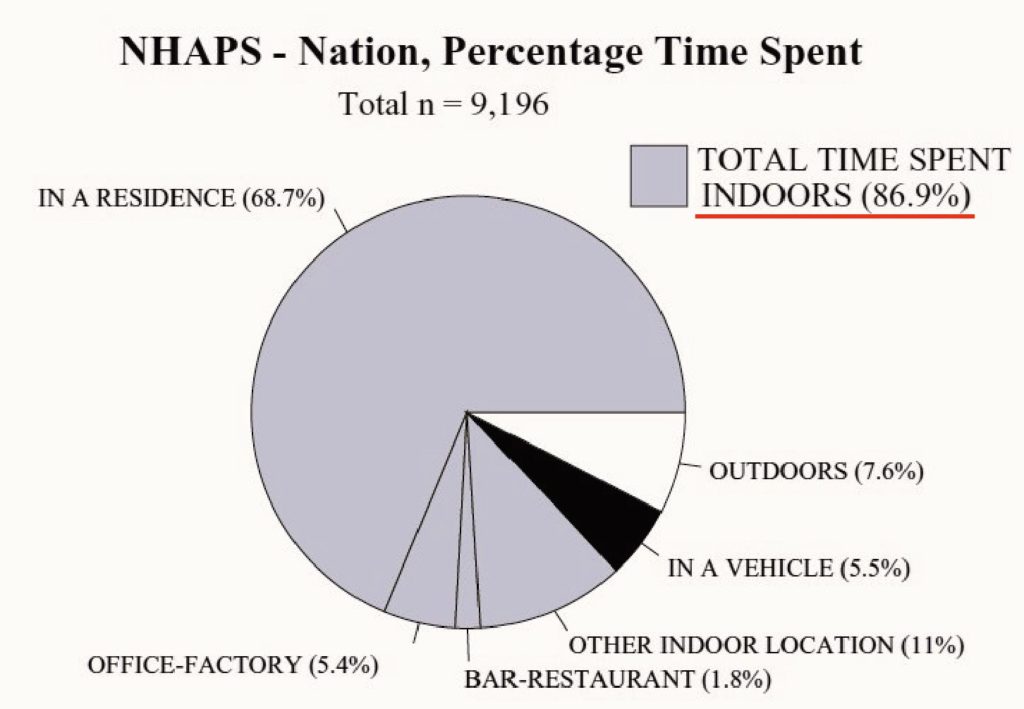

例えば、この主人公は、1日24時間の内、屋外で約3時間、屋内で約21時間を過ごしている。つまり、約9割(86.9%)の時間を屋内で過ごしている。これは米国現代人の平均的な統計データ(※1)を元にしたのであるため、個々人の職種や日本の状況では違いも大きいのであるが、割と多くの方に当てはまるのではないかと思われる。

『健康空間』はこの9割にフォーカスするものである。数字だけを見ても90%の時間を過ごす室内環境が身体に影響を与えないと考える方が難しいくらいであるが、あまり実践されてこなかったテーマである。ビル管法を遵守した建築や病院建築又は先端的なプロジェクトでは実践されている事例も見られるが、個別の設備設計などを行う事例が少ない分野(住宅や小規模建築など)では、実践例は少ない。

米国における自社ビル等での不動産事例では、不動産の3-30-300ルールがあり、公共料金(3)-家賃(30)-人件費(300)という3要素の単位面積当たりの平均的コスト($/ sqft)を示したものである。換気などの公共料金をケチりながら、最も高価な資産である人が最適な状態で働くことができないのは馬鹿げたことであるとも実感できる。(※2)

「実践」という言葉を利用したのは、実は日本でも知見自体は蓄積されているからである。例えば、室内の空気汚染度や温熱環境等に関して、空間要素(天井高さ、壁仕様、室内容積など)との関係で整理されているものは多く存在する。しかしながら、その知見を空間要素や形態にフィードバックしている事例はあまり見かけないのが実情である。(一部先端的取り組みとしては存在する。)

そこで、『健康空間』である。言い換えると、蓄積されている建築環境に関する知見を活かして、空間要素・形態へフィードバックさせることである。当然ながら設計段階でしか計画できないため、実現には設計者との共同が必要となる。心配される建設コストに関しては、空間構成要素(屋根、壁、床など)の調整が主たる手法となるため(仕上げグレードを上げるオプションも一部にはあるが)、採用したからと言って、一律に建設コストを大きくするものではない。設計上の付加価値として提供できるものと考えている。(※誤解の無いよう注記しておくと、設計業務は見た目のデザインのみを良くしようというものでは無く、また、高級仕上げを採用するだけでもない。)

『健康空間』の主なメリットをまとめると以下の通り。

- 健康に配慮した居住空間(室内環境)の獲得

- 執務空間における生産性の向上

- 建設費を大きく増大させるものでは無く、設計ノウハウとしての付加価値。(但し、コスト増を伴うオプションも存在する。)

ここでは、本テーマに関する具体例や書籍紹介、試案などを順次公開していきます。

※1)N. E. Klepeis et al., “The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A Resource for Assessing Exposure to Environmental Pollutants,” Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology 11, no. 3 (2001): 231

※2)Joseph G. Allen & John D. Macomber (2020) Healthy buildings. the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

For Guests using English, all “IDEA” pages has translated English description following Japanese description.

Introduction

After waking up at 7:00 a.m. and finishing breakfast, I spent about an hour commuting to work with checking the news in the train. After arriving at office, I complete my morning time duties. Then, I finished lunch at a restaurant about a 10-minute walk from my office. Because my afternoon work included a meeting at a customer’s office, which took 20 minutes each way. I could not finish the meeting within business time, then so had to work one hour overtime. Going home with one hour let me exhausted, but it was accompanied by a feeling akin to a little satisfaction due to well meeting result. After returning home at 8:00 p.m., it wasallowed an irreplaceable time to spend with my family.

The main contents

For example, this protagonist spends about 3 hours outdoors and 21 hours indoors out of a 24-hour day. In other words, he spends about 90% of his time indoors. Since this is based on the average statistics of modern U.S. residents (*1), it is likely to apply to a relatively large number of people, although there are many differences depending on the individual’s occupation and the situation in Japan.

The “Healthy Space” focuses on this 90%. It is difficult to believe that the indoor environment, in which we spend 90% of our time, does not have an effect on our bodies. This is a theme that has not been practiced very much. While there are some examples of buildings that comply with building codes, hospital buildings, and cutting-edge projects, there are few examples in fields where individual facility design is rarely practiced (e.g., housing and small-scale buildings).

In the case of real estate in the U.S. for company-owned buildings, etc., there is the 3-30-300 rule for real estate, which indicates the average cost per unit area ($/sqft) of three factors: utilities (3) – rent (30) – labor cost (300). One can also realize that it is ridiculous that people, the most expensive asset, cannot work in optimal conditions while skimping on utilities such as ventilation. (*2)

The reason we used the word “practice” is that the findings themselves have actually been accumulated in Japan. For example, there are many studies on indoor air pollution levels, thermal environment, etc. that have been organized in relation to space elements (ceiling height, wall specifications, indoor volume, etc.). However, there are few cases in which the findings are fed back to spatial elements and forms (some cutting-edge efforts exist). (Some cutting-edge efforts do exist.)

This is where “Healthy Building” comes in. In other words, it is to utilize accumulated knowledge of the built environment and feed it back into spatial elements and forms. Naturally, this can only be planned at the design stage, and therefore requires collaboration with designers to realize. As for construction costs, which are a concern, the main method is to adjust spatial components (roof, walls, floors, etc.) (although there are some options to increase the grade of finishes), so the adoption of this method will not uniformly increase construction costs. I believe that it can be provided as a value-added design feature. (*Note to avoid misunderstanding, design work is not only about improving the appearance of the design, nor is it only about adopting high-end finishes.)

The main benefits of “Healthy Building” can be summarized as follows

- Acquisition of health-conscious living space (indoor environment)

- Increased productivity in the office space

- Added value in the form of design know-how, not a significant increase in construction costs. (However, there are some options that do increase costs.)

Specific examples, book introductions, and trial designs related to this theme will be released here as they become available.